EDITOR’S NOTE: The network of streams and wetlands surrounding Stittsville have been changing over the past few years. Landowners say they’ve seen a dramatic rise in the amount of water on their land during a period that has coincided with Stittsville’s expansion.

In Part 1 of this series, we highlighted water issues along Flewellyn Road. Homeowners there believe that quarries are one of several factors contributing to the water changes.

In Part 2, we look at concerns of the landowners who live right next to the quarries. One of those landowners is Len Payne, who’s raised the ire of government and conservation officials for some of the changes he’s made to his property to try to drain his land. We’ll examine those issues in a later story in this series. Today’s story starts with a tour of his property between Jinkinson Road and the Trans Canada Trail.

***

ON A BRISK SATURDAY AFTERNOON IN NOVEMBER, I drive west down Hazeldean Road and turn left on Jinkinson, just before the highway. Just down the road on the left is a piece of property that belongs to Len Payne.

The front part of his property is a gravel lot with construction equipment and shipping containers. His land extends as far south as the Trans Canada Trail, where it’s mostly trees and bush. He wants to take me around the area to see some of the problems he and his neighbours have been having with water.

We hop on his ATV and drive south through his land. We cross over a shaved strip of forest that’s been cleared for the Enbridge gas pipeline. We drive by the remains of an old farmhouse and past a pile of rock that was removed when the pipeline went in. “Hope nobody’s out here hunting,” he says.

Eventually we end up at the Trans Canada Trail, driving west for a few hundred metres. There are large pools of water on both sides of the trail, and in a particularly swampy area there’s a narrow culvert crosses under the trail, protected with a mangled iron gate.

Payne says this culvert is one of the culprits for the flooding on his land and his neighbours’ properties. He says the culvert isn’t adequate to handle the water run-off from the Tomlinson quarry next door, and that there should be more infrastructure to make sure the water heads south past the trail, rather than towards his land.

“I say clean out the ditches, and if the water has to flow east, let’s get these ditches put in so the water can flow east,” he says.

***

via Google Maps

via Google Maps

LEN PAYNE’S NEIGHBOUR IS JIM VOROBEJ. He’s owned the land since 1972. He’s 85 years old now. He’s been trying to sell the land for the past five years but nobody’s buying.

“The quarry started, the beavers moved in, and everything. It used to be pasture, but it’s drowned now,” he says.

A culvert under the trail owned by the city is often blocked, and Vorobej doesn’t think the city clears out the beaver dams frequently or fast enough.

Vorobej sounds upset when I talk to him on the phone, and frustrated by what’s happened to his land.

“If they opened the beaver dams, it would go back to how it used to be,” he says.

“It was beautiful. Nice trees, beautiful land.”

***

THE TOMLINSON QUARRY IS JUST WEST OF VOROBEJ AND PAYNE’S PROPERTIES, and is one of several in the area. On some days of the year, the quarries combined will pump millions of litres of water into the various streams, wetlands and ditches that make up the Jock River watershed.

Tomlinson’s quarry opened in 2002 and has been operating fairly consistently since 2006. I’ve seen Tomlinson’s big red smokestack from Highway 7, but until recently I didn’t know how many quarries were in the are or what exactly they were doing.

“The number one thing that we do is we’re building a hole into the ground,” says Scott Berquist, the engineer responsible for Tomlinson’s aggregate operations. He says limestone gets extracted from the ground and is used in construction as road beds, or for concrete or asphalt.

“Any water that would be in the watershed in that area, any run-off, any precipitation is going to be collecting in this hole… You’re just trying to pump the water out that gathers in there because we can’t operate our equipment. We can’t work in the water,” he says.

A pump removes the water just like a sump pump in a basement. Quarries like Tomlinson need two permits from the Ministry of Environment to operate: a permit to take water that regulates how much they can pump per day, and a sewage permit that outlines where the water should go. The permits also have requirements for monitoring water quality and groundwater levels.

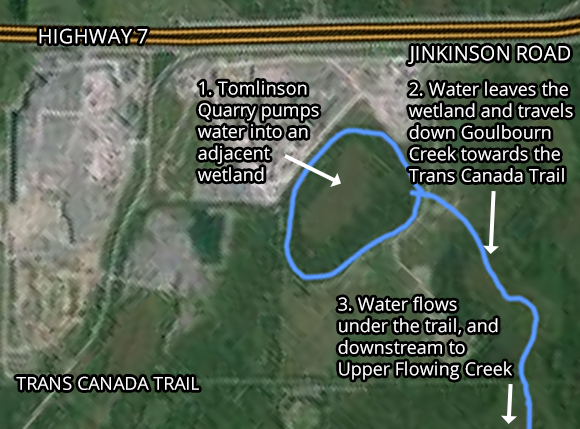

In the case of Tomlinson, water gets pumped into a wetland on their property that serves as a sort of holding reservoir, releasing the water gradually into the watershed.

From the wetland, water exits into the Goulbourn Creek before making its way under the Trans Canada Trail to Upper Flowing Creek, crossing Fernbank and Flewellyn and eventually emptying into the Jock River. (Most of the other quarries on Jinkinson Road empty into the Hobbs Drain, a watercourse further west.)

Before there was a quarry, the Goulbourn Creek was barely a trickle for most of the year. Payne says the higher volume of water coming from the quarry has attracted beavers to the area, contributing to the flooding on properties along the north side of the trail.

Further south near Flewellyn, landowners like Michael Erland believe the extra volume of water from the quarry is part of what’s causing flooding on their property. He says the drainage infrastructure was never meant to handle millions of litre of water from quarries.

***

I’VE TALKED AND TRADED EMAILS with an official from Tomlinson, as well as an engineer, a biologist, city and provincial representatives and environmentalists about the issue. So far, nobody’s been able to say for sure what effect the quarries have on water in the area. Their feedback and other studies show that there is certainly more water coming from the quarries, but it is unclear exactly how much water or what effect it is having on the surrounding land.

An engineering report commissioned by the City of Ottawa in 2010 identified “aggregate resource operations” as one of several factors contributing to increased flooding in the Upper Flowing Creek drainage area. But there does not appear to be any data available to quantify that effect.

The Tomlinson Quarry is the only one that is supposed to discharge its water into Upper Flowing Creek. It’s licensed to pump up to 7-million litres of water per day out of the quarry and into the neighbouring wetland pocket. That’s a lot of water: about seven Olympic swimming pools of water, to use the standard comparison.

“It sounds more than it is, and in actual fact it’s a worst case scenario,” says Berquist. “There would never be a situation where you’d pump out that much every day. You just wouldn’t.”

In 2014, as of November 5, they pumped water for 72 days, at an average of three million litres per day over that period. The highest amount pumped in a single day was six million litres on July 3.

Every quarry has to keep records of exactly how much water they pump each day, and provide the report to the Ministry of Environment. Those records are only available to the public via a freedom of information request. The quarries aren’t responsible for monitoring downstream impacts on water flows or water levels.

A July 2000 report by Golder & Associates that was used for the original quarry permit does address some of the expected effects of increased water flow:

- The annual flow of water from the quarry to the receiving wetland was predicted to gradually increase from the existing 17 litres per second to 79 litres per second as the quarry fully develops over more than ten years.

- “Goulbourn Creek, an intermittent stream at present (2000), is likely to become a perennial watercourse”. Flow would vary widely based on the season.

- “It is unikely that the receiving wetland water level with rise more than 0.5m to 1m.”

- “Outflow from the receiving wetland could significantly incrase if water level rises by approximately 0.5m to 1m”.

Kris Marentette, a Senior Hydrogeologist from Golder & Associates provided StittsvilleCentral.ca with a chart showing water levels measured in the wetland. They’ve fluctuated considerably over the years but haven’t reached that critical “0.5m to 1m” increase. He says the numbers are within expected thresholds.

Marentette also says that given the size of the wetland in the area, and the amount of water being discharged, the outflow down the Goulbourn Creek (the amount of water leaving the wetland) is minimal.

***

THE RIDEAU VALLEY CONSERVATION AUTHORITY (RCVA) MONITORS WATER LEVELS every six years as part of a regular Jock River Watershed Study.

The most recent report is from 2010. The Flowing Creek catchment area that Tomlinson’s quarry empties into, is 97.3km long and drains an area of 53.8 square kilometres, or nearly 10% of the entire Jock River Watershed.

Although the report notes the quarry operations in the area, there is nothing in the report about water levels or flow. That data is listed as “Not Applicable”. The report does note that the catchment is a “candidate for an Integrated Water Resources Management Strategy to address potential conflicts in water management”.

“I know we don’t have the resources to collect as much data as we would like, but we collect as much as we can in the watershed,” says Don Maciver, director of planning with the RCVA. “There is some controversy over resource management issues in that area and it’s been going on for quite some time.”

***

IT LOOKS LIKE THE NEXT OPPORTUNITY TO SEE DATA on the possible effect of quarries and other factors on the watershed will come in 2015, when the City will present preliminary results of the Flewellyn Cumulative Effects Study. That study is designed to “identify the changes to the drainage in the area resulting from, but not limited to, the effects of road construction, private drain works, municipal drain maintenance, and discharge of water from quarries.”

Those results are eagerly awaited by landowners like Payne, Vorobej, and others who we met in Part 1 of this series, who are looking for answers about why their land is flooding, and action to deal with it.

Payne acknowledges that the quarry is operating legally within the limits set out in its permits. He just wants more oversight and maintenance on the infrastructure that carries the water away once it leaves the Tomlinson property

“They got their approval and they’re permitted to pump into wetland. For all of this stuff to work, every landowner has to do their part and they have to keep the ditches clean, the beaver dams clean, and let the water go. Or we can’t have any of this commercial activity going on,” he says.

***

In the next article in this series, we’ll dive into the province’s Provincially Significant Wetland (PSW) designation and the concerns that critics have about the program.

We’d like to hear from our readers on this issue. Add your comments below or email feedback@stittsvillecentral.ca

The TC trail down that way often is flooded too, however that is mainly due to beaver activity. It makes me wonder if beavers may be playing a role in this case too.

Beavers are definitely a factor. One of the points that Vorobej made to me was that beavers are attracted by all the extra water in the area. When Goulbourn Creek was just a trickle, the beavers weren’t interested. But now that there’s more water flowing through it, they are very interested.

Seems like another person having to deal with shady business deals that destroys the way of life they have lived for years and no one cares as long as there is lots of money to be made.